Slowing growth and depressed commodity prices threaten to unleash a wave of restructurings following years of leverage.

The Asian restructuring sector has endured something of a patchy time in recent years. Workouts have struggled to reach completion or have been concluded after drawn-out timelines with deep discounts on the dollar and ultra-long maturity extensions. With more and more Asian companies scrambling to service debt, however, a boom in regional restructuring beckons.

“We are going to see a lot more debt restructuring in Asia over the next few years, more than we have seen over the past few years,” said Michel Lowy, co-founder and CEO of independent fixed-income specialist SC Lowy.

“We are entering a new era in Asian debt restructuring, one which, arguably, will be on a scale we haven’t seen in several decades. People don’t appreciate the level of deleveraging that is required.”

“It is difficult to judge the extent of the damage that has been inflicted on companies in the region by slowing and over-leveraged economies, but there is no doubt that there is a lot of pain caused by exposure to the commodity cycle and its anchor in a slowing Chinese economy.”

Investors have hardly had to worry about the threat of non-payment in recent years. The default rate among Asia-Pacific companies last year reached its lowest since the financial crisis. According to Standard and Poor’s, defaults for all of Asia-Pacific fell to just 0.26%, from 0.42% in 2013 and 0.29% in 2012. Low-grade defaults below the BB+ level came in at a rate of 1.18%, versus 2.01% the year before and 1.41% in 2012.

“Part of the reason is that the bankruptcy regime in Asia hasn’t really changed over the past 20 years, and the kind of control of the workout process you get in developed markets is not there.”

Robert Schmitz, head of debt advisory at Deloitte in Singapore, recently described the Asian workout landscape as “a tough place to be in” due to the paucity of large restructuring deals that have made it across the line in recent years. Schmitz himself presided over one of Asia’s most drawn-out restructurings, for Indonesian shipping company Arpeni Pratama, which finally closed in 2012 after almost three years of negotiation.

“We are entering a new era in Asian debt restructuring, one which, arguably, will be on a scale we haven’t seen in several decades. The underlying dynamic is one of disinflation, deflation and deleveraging and, in my opinion, the optimists will get hurt. People don’t appreciate the level of deleveraging that is required,” said Schmitz.

The Arpeni deal was a nail-biter, involving an exchange of US$141m of debt and US$100m of secured loans via reverse Dutch auction, and a US$25m reduction in its balance sheet. Eventually, it involved an average purchase price of 18 cents on the dollar – one of the most brutal haircuts seen in an Asian debt restructuring, but, at least, the company was saved as a going concern.

Schmitz has observed that the debt-for-equity swap, which should rightly be regarded as a crucial tool to smooth the passage of restructuring, is difficult to employ in Indonesia when bank creditors are involved. This is because internal statutes prevent Indonesian banks from holding equity on their books for more than two years. Interestingly, however, a crucial enabler of the Arpeni workout was majority shareholder and founder Oentoro Surya’s injection of US$75m of fresh equity.

Another standout feature of the Arpeni restructuring, likely to be the cookie cutter approach in Indonesian debt restructuring, was the invocation of Chapter 15 bankruptcy filing in the US courts so that any newly issued debt involved in the restructuring would be subject to Indonesian rather than US jurisdiction.

That may not be music to the ears of offshore creditors given the capricious nature of Indonesia’s courts, but is seems that the administration of President Joko Widodo is determined to improve transparency across the country’s commercial and legal complex.

International investors will certainly be hoping that the days when a company can file to have overseas debt declared illegal – something that happened in the gargantuan workout of Asia Pulp and Paper in the early years of the last decade, which at US$14bn was Asia’s biggest – are definitively in the past.

An interesting phenomenon that may yet gain traction in Asia is the concept of the “pre-emptive workout”, where a company struggling to service its debt hires a restructuring adviser early on to avoid dealing with the all-too-familiar workout scenario of default, stock suspension and seeing its debt hoovered up by vulture funds extracting their maximum pound of flesh.

Indonesian coal-services provider Bukit Makmur Mandiri Utama (Buma) did just this in March 2013, when it hired Deloitte to advise on its debt, a couple of years after closing a US$800m seven-year loan and just as the commodity super cycle was beginning wreak havoc on the global coal sector.

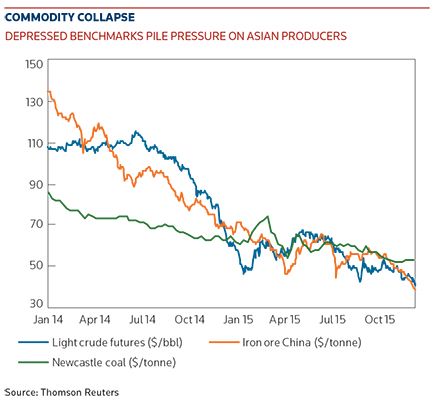

The coal price was around US$130 per tonne when the loan was closed, but had collapsed to around US$92 per tonne when restructuring negotiations began, pulling back Buma’s revenues and forcing the company into a strategic rethink. Buma’s management correctly projected a worsening of business conditions – the coal price has sagged further to US$55 per tonne of Australian thermal coal, Asia’s coal benchmark, representing an eight-year low – and, although the company did not default on its debt, it sought to restructure the US$603m left on the loan after amortisation.

“Buma’s workout was rigorous and severe and we had to be extremely tough in terms of cash sweeps and what could be afforded by the company, otherwise there was the risk of the whole deal falling apart. In the end, the terming out bought the company breathing room, but the outlook for the coal market remains testing,” said Schmitz.

The company finalised new terms on the loan in April 2014 and signed off on the restructuring in August that year, extending the final maturity to December 2019 from March 2018, introducing a series of cash sweeps, which were not included in the original covenants, and pushing the margin to Libor plus 400bp–500bp from plus 375bp.

This is, perhaps, a sign that, despite the troubled industry background, when it comes to terming out creditors are still likely to push for a high internal rate of return, the risk of default amid higher leverage levels notwithstanding. Buma’s covenanted debt-to-Ebitda ratio on the original loan was 3.5 times and 4.16 times, following the restructuring.

The debt revamp managed to pull in the 100% consent required in the original indenture and managed to meld the interests of a wide range of debt holders, including Singapore sovereign wealth fund GIC, as well as 12 local and international banks.

“Buma’s workout should be seen as the gold standard for restructuring and, as various sectors in Indonesia from coal through to telecoms and shipping are struggling, it’s the one that struggling corporations should look to. Act early, complete quickly and protect your reputation with creditors to ride out the cycle and avoid getting wound up,” said a Hong Kong-based loan banker.

However, others, including Michel Lowy, take a different view: “Pre-emptive restructurings are too often in a sense not real restructurings per se, but more a ‘kicking the can down the road’. The real long-term issues tend not to be dealt with.”

Haircut or liquidate?

The great dichotomy that divides the world of the debt workout specialist is whether to attempt to preserve an enterprise as a going concern via debt terming out and establishing a haircut acceptable to creditors, or to opt for a winding-up and the liquidation of assets.

Hong Kong-based workout specialist Borrelli Walsh adopted the latter route in the winding-up of Singapore-based Jurong Aromatics Corp (JAC). JAC, which operated one of the world’s largest petrochemical plants in Singapore, took a hit hard from collapsing prices for oil-related products, as well as slowing demand in Asia, forcing it to cease operations at the end of last year.

Back in 2011 a US$1.56bn financing was put in place, co-ordinated by ING and Royal Bank of Scotland and joined by 11 banks, with a variety of credit wraps from Korea Trade Insurance and Export-Import Bank of Korea. BNP Paribas was on the financing and, in early October, appointed Borrelli Walsh as receiver. The total value of the restructuring is estimated at US$2.2bn.

According to the latest records from 2013, JAC has US$1.53bn of liabilities and US$68.7bn of accumulated losses. It faces secured claims from British Petroleum, Glencore and SK Energy, the latter two among the original sponsors of the JAC plant. JAC’s biggest shareholders are South Korean chaebol SK Group with 30%, while China’s Jiangsu Sanfangziang Group holds 25% and Glencore holds 10%.

“The JAC receivership is a stark reflection of the impact the commodity super-cycle is having across a range of businesses in Asia. The deflation of commodity prices and related products is making it challenging not only to service debt, but also to retain viability as an ongoing concern,” said Schmitz.

“There is a big overhang of redemptions and it is not clear just where the funds will come from to refinance them. If you look at the resource complex of secondary debt in Asia, much of it is trading in the 50-60 cents range and it’s not clear yet whether the vulture funds will move in to snap paper up or whether they regard it as catching a falling knife,” Schmitz said.

Michel Lowy, whose firm has its origins in distressed debt trading, believes global funds are still cautious on Asia.

“As for the levels of distress we see in Asian secondary debt, prices are down, but we are not seeing very much buying. Global hedge funds, real money and private banks are more interested in picking up debt in the developed markets of the US or Europe,” said Lowy.

“Part of the reason is that the bankruptcy regime in Asia hasn’t really changed over the past 20 years, and the kind of control of the workout process you get in developed markets is not there. Owners often stand in the way and the courts also tend not to fall on the side of creditors.”

Refresh and redo

With the commodity cycle remaining in a trough because of weakening demand in Asia, amid a slowing China, there is the prospect that “workouts of workouts” will emerge, as companies that have restructured their debts and rejigged their capital structures will be unable to honour the original terms of the workout.

“We will see ‘refresh and redo’ because the global economy is in bad shape and more than likely to get worse,” said Schmitz.

One such company is Arpeni, which is engaging in a second round of restructuring after the anticipated turnaround in the shipping industry failed to appear. This echoes one of the headline defaults of 2014 from Indonesia’s Bumi Resources, which signed off on a distressed exchange last year only to return to default status after it failed to redeem its convertible bonds.

Coal-miner Bumi is sitting on debt of around US$4bn and, in a move in October, which numerous creditors have rejected, proposed converting some US$2.7bn of the debt on which it is in default into equity, plus the issuance of US$1.2bn of new paper. A complex scheme of issuance, involving the offer of new debt tranches in exchange for paper due in 2016 with a haircut in excess of 60%, is on the table, via restructuring adviser FTI Consulting, with the remaining principal to be converted into equity.

Much seems to depend on projected coal prices, but, with China’s GDP growth rate likely to fall further and PRC demand crucial to the price of coal, the trajectory is less than auspicious.

“You can agree to a restructuring today, but when there’s one key variable – in this case the coal price – which looks unlikely to provide the magic bullet, then it looks probable that down the line you will end up having to restructure the restructuring,” said a Singapore-based loan banker.

If there is to be a restructuring bonanza in Asia over the next few years, the source seems likely to be China, where the government’s efforts to reform its bloated state-owned enterprise sector, and, in the process, allow commercially non-viable companies to fail, point to a wave of defaults. Outside the SOE sector, many over-leveraged Chinese companies are facing challenges in debt service.

In recent months, Winsway, Hidili and Shanshui Cement have all missed coupon payments, with Shanshui entering formal restructuring after filing in November in the Cayman Islands to have the company wound up and accelerating payments due on its 2020 US dollar bonds.

Market participants will be closely watching the Shanshui workout for evidence that China’s bankruptcy laws honour the capital structure. There have been defaults before, most notably in 1998 when state-owned Gitic missed an 8.75% coupon on bonds of US$200m in the first default from China in almost 50 years. Also, overseas creditors of Asia Aluminum, Sino-Forest and LDK Solar wore heavy losses on their investments, following defaults after the global financial crisis. They discovered that they had no recourse to assets held in China, having invested in bonds issued offshore.

The haircut on payment-in-kind notes of Asia Aluminum was a stratospheric 97%, following the company’s liquidation in 2009. The hope is that China has moved on from that experience and understands the need to reinforce the aspiration, if not the reality, that its bankruptcy practices adhere to Western standards.

Chinese real-estate developer Kaisa Group has sounded a brighter note, having proposed the restructuring of its offshore straight and convertible bonds of US$2.5bn via a cut in coupons, partial payment in kind and a maturity extension that appears to avoid a drastic principal haircut and treat its various groups of senior creditors as equals. Arguably, that is the right precedent and the Asia-facing investment community will be hoping it is the benchmark for future Chinese debt restructurings.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here.