Fixed-income investors are turning attention to domestic Chinese bonds in their search for an early foothold in the world’s fastest-growing debt market.

Global investors in Chinese debt are expecting a steady supply of issuance in 2014 as PRC regulators encourage companies to shift away from banks and towards the bond markets for financing.

Mainland ambition

Source: REUTERS/Jason Lee

A student holding a tyre takes part in an event at an Olympic education model school in Miyun County of Beijing.

Many of these bonds will be issued offshore in the growing number of Dim Sum markets and in the international debt markets, as regulators worried about bloated credit conditions have raised rates in China, making it more expensive for companies to raise funds.

A small group of investors have their eyes on a far larger bazaar for PRC debt, however – China’s US$4trn onshore bond market, the third largest in the world behind only the US and Japan.

While it remains largely closed to most foreign investors, China’s large, liquid debt market should not be ignored and will soon be the key to global bond investing, these investors say.

In fact, if China’s government bond market, which alone is just under US$3trn, was included, it would make up about 12% of any typical global bond index, according to Hayden Briscoe, director for Asia Pacific fixed income at AllianceBernstein.

That figure will become more important if, or rather when, the renminbi becomes internationalised, which it is rapidly on pace to do, investors say. Already, the renminbi is the eighth most traded currency on the globe, according to electronic payments firm Swift.

In Briscoe’s opinion, once the currency is fully internationalised, any investor tracking a global bond index will need to allocate 12% of its capital to China debt. Most investors now have zero allocation to China “and that’s the wrong number,” he said.

Sovereign wealth funds, he pointed out, were investing about 5% to 10% of their global debt allocation in China to get exposure to the renminbi. These funds were receiving yields on China’s 10-year debt of about 4.5%, compared with about 3.6% for Spain, and 3.7% for Italy – debt arguably issued by governments with far less safe, deep and liquid bond markets, Briscoe said.

“Up to 10% seems to be the right number to us,” he added. “Institutions need to start researching [China’s] government bond market and how to get access to it.”

Chinese squeeze

Andy Seaman, a partner at Stratton Street Capital in London, and manager of the Stratton RMB Bond Fund, has a similar view.

“People have more exposure to Hungary than China, even though China is 50 times the size,” said Seaman, who expects China’s bond market to rival the US Treasury market in size within five years. “Most of the countries in Asia are creditors, China in particular, and most people have allocated their fixed income to debtor nations.”

The problem, of course, is that foreign investors currently have very little access to China’s onshore debt. The investment quota under China’s renminbi qualified foreign institutional investor programme, which began in 2010, allows selected investors to buy up a total of up to Rmb270bn in stock and bond investments on the mainland – less than 3% of the Rmb23trn market capitalisation of shares traded in Shanghai and Shenzhen.

Stratton Street Capital has applied to be among investors granted a slice of a slim Rmb80b RQFII quota granted to investors in London.

“In the context of a US$4trn [bond] market, that’s quite small,” Seaman said, but “that’s just a first step and eventually that will get opened up.”

Like Briscoe, Seaman’s initial purchases in China debt will be government bonds, not corporate paper, which is more difficult to assess.

“The corporate market will be priced relative to the government in any case,” Seaman said. “You need to understand the government bond market first.”

Dim Sum

Similarly, both Seaman and Briscoe eschew the offshore renminbi market, more commonly known as the Dim Sum market, describing it as overvalued.

“We have yet to find a single issue we like: it’s too expensive, too illiquid and too small,” Seaman said. “When you compare it to the domestic Chinese bond market, it doesn’t offer any value at all.”

“Institutions need to start researching [China’s] government bond market and how to get access to it.”

Seaman buys investment-grade corporate bonds that he evaluates as undervalued from across the Middle East and Asia for his renminbi fund, and overlays the holdings with a renminbi forward currency hedge. In early February, the fund held 12 credits from China, Hong Kong and Singapore, yielding 3.23% to 7.00%.

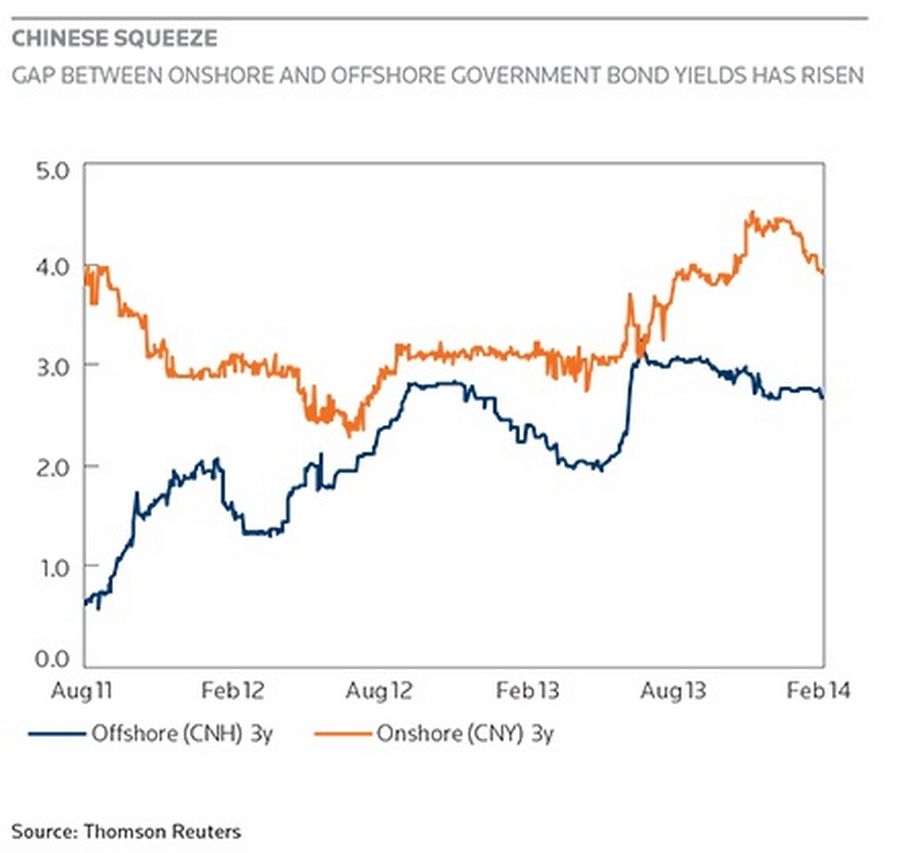

Briscoe, likewise, invests in other Asian bonds and hedges back into renminbi in AllianceBernstein’s Dim Sum fund. That is because demand outstrips supply, pushing yields on three-year Dim Sums 150bp lower than yields on Chinese government bonds.

“So, for us, there’s an arbitrage for issuers, not for investors,” he said.

China’s National Development and Reform Commission reportedly is allowing more issuers to sell offshore renminbi, and Briscoe expects this to push up Dim Sum yields. The influx would bring the offshore renminbi supply/demand equation into balance, and yield spreads between the two markets would narrow, he said.

The Dim Sum market is expected to grow to CNH180 to CNH 250 billion this year, excluding CDs, because of rising onshore funding costs and the acceleration of RMB internationalisation, according to Rajeev De Mello head of Asian fixed income at Schroders Investment Management.

Most investors, however, are not focusing on China’s local government bond market just yet. One reason is the lack of familiarity with local government entities. Another is the likelihood of higher yields on the mainland, meaning prices will go lower, as the government seeks to stem credit growth, DeMello said.

Instead, Schroders will look at the offshore dollar market, which will provide a cheaper funding source for Chinese state-owned enterprises and other companies than the mainland.

“We will have the luxury to be quite selective because of what we think will be the breadth and depth of issuance,” De Mello said. “We are not rushing to invest; we are carefully looking for the names and the prices that offer good value.”

Similarly, Neeraj Seth, managing director and head of Asian credit in BlackRock’s Alpha Strategies Investment Group, remains interested in China’s G3 bonds, but he studies underlying fundamentals and does not take credit ratings at face value.

Seth is looking closely at Chinese property bonds in the wake of a selloff in the sector, and a repricing of Double B credits after some Triple B issuers sold bonds at wider-than-expected spreads. “We had gone neutral going into the year, and underweight in the high-yield sector, and we are re-evaluating that,” he said.

However, volatility and rising spreads in the US dollar market might push more Chinese issuers, to the Dim Sum market, which will be the least expensive place to issue, said Bryan Collins, manager of Fidelity WorldWide Fund RMB Bond Fund.

Also, while the Dim Sum market might not offer the highest yield, investors will continue to like it because the risk and return profile of the market is second to none, Collins said. It is also a mostly short-duration, investment-grade market with relatively low volatility, he added.

“The credit risk is a lot lower than US dollar high yield,” Collins said. “Total return in renminbi of 3%, 4% is still pretty attractive in the grand scheme of things.”

To see the digital version of this report, please click here.