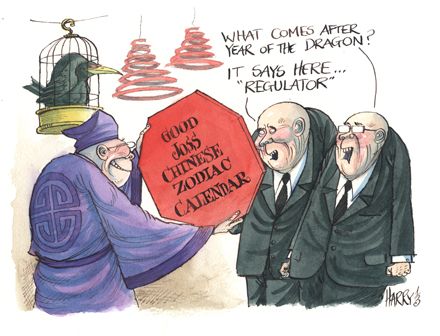

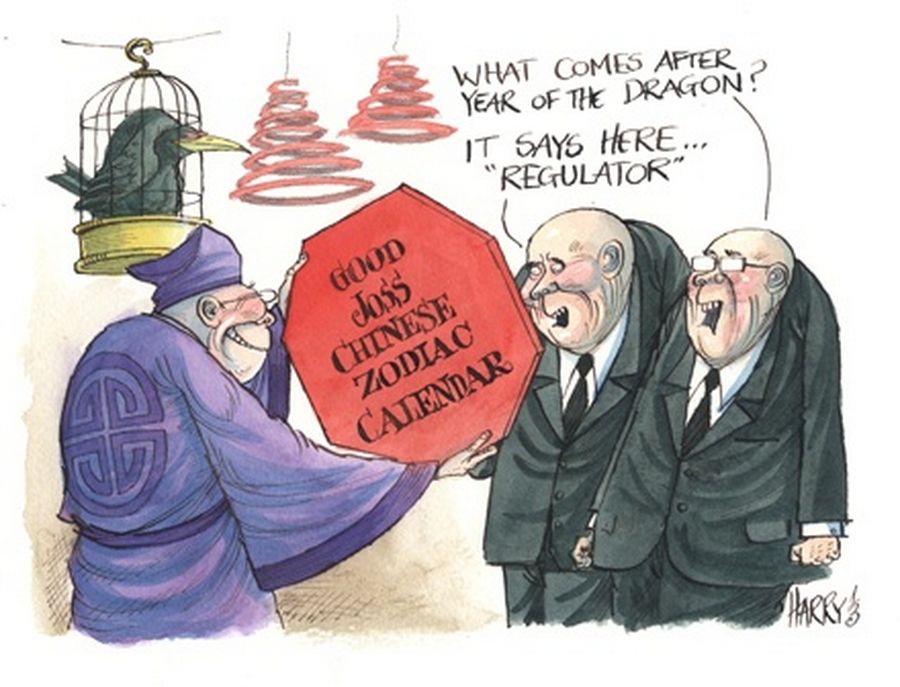

Asian regulators decided the outcome of more capital markets deals in 2013 than any investment banker, with efforts to improve liquidity and transparency across the region. The real fruits of their labours, however, may become clear only in years to come.

Political capital

Regulators across Asia have set out to improve governance and transparency in their capital markets, but regional experts worry they could create a host of self-defeating distortions if long-standing structural contradictions are ignored.

The biggest changes have been in China, where the Year of the Snake may go down as one of the regulator. The Chinese Government has either proposed or followed through on a raft of economic and financial reform measures in its capital markets. Authorities in India and the Philippines also have been working hard, particularly to hone their respective free-float rules.

In all jurisdictions, regulators are struggling to strike a balance between ensuring ample flexibility to encourage investments and growth, while discouraging the kinds of inflows or speculative activity that can threaten the stability of a financial system. The question for investors in Asia is whether or not they are likely to get that balance right and if they can find opportunities during the regulatory flux.

For China, a lively debate has ensued over what measures the government should undertake to wean the country off its investment-fuelled economic model, set it on a path towards consumption-driven growth and, finally, establish a regulatory regime to enable international investors to trust fully its often-opaque capital markets.

“If the zone is walled off from the rest of China, then the attraction of investing in it for foreign companies should be fairly limited.”

“China’s government is good at building roads and airports, and pouring concrete, but, in terms of winning people’s trust, it falls short. Trust in the legal system, openness – these are not things that the Chinese Government can easily legislate for,” said Mark Williams, chief Asia economist for Capital Economics, an independent macroeconomic research company.

In 2013, securities market regulations in the PRC continued to evolve, as the China Securities Regulatory Commission persisted with the suspension of any new IPOs on either the Shanghai or Shenzhen stock exchanges, while it worked to restore confidence in the listing process.

The suspension of listings in China drove some listings to the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong. The SEHK, meanwhile, introduced changes to listing rules that significantly increased the onus on IPO sponsors to ensure listings were compliant and credible. One measure has made sponsors criminally liable for the contents of their IPO prospectuses.

The PRC bond market is also slowly opening, with 17 central banks now authorised to invest in Chinese debt, according to Stephen Green, head of research for Greater China at Standard Chartered Bank.

“These rules are engendering resentment and, practically, people are avoiding dealing with US counterparties. Even the largest Asian banks are struggling, since they haven’t sorted out the implications of Dodd-Frank compliance. Compliance costs outweigh any revenue you can make.”

While the number and volume of domestic Chinese bond sales are increasing, the PRC has yet to address the problem of having two major bond markets under the jurisdiction of separate regulators in the People’s Bank of China and the CSRC.

The regulatory split could easily nullify the impact of any well-meaning reforms, exacerbating the tensions that animate an already-dysfunctional market.

“Issuing lots of bonds does not a bond market make — since a bond market is about pricing risk,” said Patrick Chovanec, chief strategist at Silvercrest Asset Management.

“If there’s no connection between risk and return, you’re going to have misallocation of capital,” Chovanec said. “The government still defines risk, and decides what goes bad and what doesn’t.

The market is not pricing in the real economic risks on investments.”

Third Plenum reform

In November, the Third Plenum of the Communist Party’s 18th Central Committee resulted in a long-awaited statement on government policy priorities for the next decade. After a vague initial communiqué, a more detailed plan soon followed, sparking considerable market optimism.

“It’s the first time this century that China has produced an economic reform plan that’s comprehensive and addresses all of the challenges it faces,” said Capital Economics’ Williams.

The plan will allow the establishment of private banks for the first time, will liberalise interest rates, beginning with a deposit insurance scheme, and will move towards opening the current account, although full liberalisation remains some way off.

The PBoC has also promised, once again, to stop intervening in foreign exchange markets, despite having purchased tens of billions of dollars and other currencies in forex as recently as September. The CSRC announced plans in late November to streamline the IPO process and to move towards a system that would give more power to market forces.

The focus now shifts to whether or not China will follow through and implement real reform.

“There’s reason to be optimistic, since the Communist Party would not have been able to publish this comprehensive plan if it hadn’t first got backing from key interest groups,” Williams said.

Yet, some market players are more cautious, due to the complicated tensions and contradictions that plague China’s economy.

“The obstacles to seeing these reforms through aren’t simply political,” said Silvercrest Asset’s Chovanec. “They’re practical and they change the dynamics of the Chinese economy in ways that could prove very disruptive.”

The plenum also noted that problems in the economy were interlinked and needed to be tackled simultaneously. “That, of course, makes reform much, much harder,” said Williams of Capital Economics.

“The old model of Chinese reform is to cross the river by feeling for stones, taking it one step at a time. This time, the leadership will have to act on multiple fronts,” he said.

Free Trade Zone paradox

In an earlier sign of reform, China launched the pilot Shanghai Free Trade Zone as a beachhead for foreign companies. In early December, the PBoC provided some details on the scope of the reforms.

The central bank said the initiatives will include regulations allowing foreign companies with subsidiaries in the zone to issue renminbi-denominated bonds. Also, foreigners in the zone will be able to buy and sell Chinese stocks and bonds directly, and Chinese individuals in the zone will be able to buy overseas financial products without being a Qualified Domestic Institutional Investor.

However, some economists identify a contradiction embedded in the Free Trade Zone model. The government wants to separate the zone from the rest of China to allow it to experiment with different models for reform, but that will limit the size of the potential market.

“If the zone is walled off from the rest of China, then the attraction of investing in it for foreign companies should be fairly limited,” said Capital Economics’ Williams.

Another major problem would be the considerable opportunities for regulatory arbitrage in the zone. Since any Chinese bank branch can serve customers anywhere in the country, liberalising interest rates in the zone could allow banks to offer higher deposit rates than they could outside, thereby leading to a rapid draining of deposits from the rest of the banking system.

In fact, China saw a considerable liquidity squeeze in June, when interbank lending rates spiked to record highs on indications the US Federal Reserve would roll back quantitative easing. The PBoC seemed reluctant to come to the rescue.

Some claim the central bank let the squeeze unfold to rein in irresponsible lending in the so-called shadow banking sector, which has flourished in China to service borrowers that large, state-owned banks ignored.

“Shadow banking is not separate from the formal banking system, but is part of it, and the distortions in the formal banking system carry through to the shadow banking system, as well,” said Silvercrest Asset’s Chovanec.

China’s banking system had been in a state of crisis since the June squeeze, and the PBoC had had to inject TARP-like sums into the banks just to maintain liquidity, Chovanec added, referring to the US bank bailout known as the Troubled Asset Relief Program. Volatility and intermittent rate spikes persist in the interbank lending market.

Beyond the Great Wall

China certainly has not been alone in fine-tuning its regulatory regime this year. The Philippine Stock Exchange has enforced a 10% public float rule, while the Securities Exchange Board of India, or Sebi, has also adopted significant changes, including enforcing an increase in the minimum public float of listed private sector companies from 10% to 25%.

Sebi has also streamlined alternative investment funds regulation and adopted rules allowing companies to trade their own shares without requiring listing.

“Sebi is trying to make the market more efficient, increase disclosure and curtail fraud and fraudulent practices, and increase liquidity for small and medium size companies,” says Kartik Ganapathy, a partner at law firm Induslaw.

While it is too early to pass judgment on the success of the reforms, some believe they are necessary steps towards the longer-term goal of the rupee’s capital account convertibility.

In addition to the reforms in Asian markets, significant changes in the US, such as the implementation of new Dodd-Frank derivatives rules, coupled with the EU’s European market infrastructure regulations, are hampering the development of an integrated over-the-counter derivatives markets in the Asia-Pacific and elsewhere.

Fragmentation has occurred as the US and the EU apply respective rules requiring OTC derivatives involving related counterparties to trade on swap-execution facilities or be reported to trade repositories and cleared with specified clearing houses, according to Chin-Chong Liew, a partner at Linklaters.

“These rules are engendering resentment and, practically, people are avoiding dealing with US counterparties,” Liew said. “Even the largest Asian banks are struggling, since they haven’t sorted out the implications of Dodd-Frank compliance. Compliance costs outweigh any revenue you can make.”

In the end, difficulties with derivatives show that, like other markets and asset classes, the efficacy of regulation is often vulnerable to external whims. Some investors may avoid regulatory plays altogether, given the complexity and unpredictability of reform execution.

“We normally don’t make bets on policy and political outcomes,” said Peter Boodell, portfolio manager and founder, Boodell & Company Capital Management.

“In general, our businesses often have little to do with politics. The policy-driven investment arena is a difficult one, so we’re looking for businesses that can compete on their own merit.”

To see the digital version of this report, please click here.