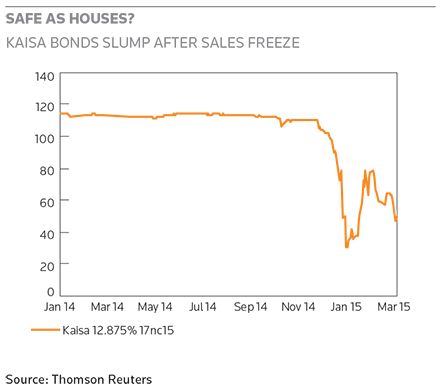

IFR ASIA: To open the discussion, I’d like to raise the issue of Chinese property developer Kaisa, which almost defaulted in January after local authorities blocked its sales. How significant is this to the wider market?

Ying Wang, Fitch Ratings: First of all, I think we need to make it clear that this is idiosyncratic. It’s not driven by the company’s fundamentals, or by the company’s ability to execute its sales. It’s primarily driven by politics. I’m not saying other property developers don’t have these kinds of issues, but this is different.

The thing that we have been watching very closely is how the offshore bondholders are positioned in this kind of event. Obviously, everyone knows that offshore bondholders are structurally subordinated to onshore creditors, but investors are probably not pricing this kind of risk correctly. You can see very clearly from this event that onshore creditors were in a rush to take action. They were requesting onshore assets and bank accounts be frozen – not just in Shenzhen, but in other jurisdictions, as well, where Kaisa has trust products, which are secured, or other bank loans. There’s just not much that offshore bondholders can do except sit on the sidelines and watch.

It is a unique event, driven by politics, but, on the company’s side, there is very little disclosure and transparency. So, this is something that investors – and rating agencies like us and other market participants – need to be reminded of from time to time.

IFR ASIA: Does Fitch rate Kaisa?

Ying Wang, Fitch Ratings: No, we don’t rate Kaisa.

IFR ASIA: One of the things I’ve noticed is that there are conflicting rating actions going on at the moment. There was a note from Standard & Poor’s on February 9 that said it remained in selective default and warned investors that risks remained incredibly high. On the same day, Moody’s put one out that said its Ca rating was on review for an upgrade. Who’s right? Are bondholders safe to assume that the danger has passed?

Ying Wang, Fitch Ratings: Well, rating actions are always a combination of facts and reasonable assumptions. That’s why you can have different commentaries coming out, and it’s very natural. We don’t rate Kaisa, so I can’t say what the correct rating should be, but, obviously, Sunac’s proposed investment in Kaisa is a positive development. It’s hard to speculate whether this is driven by Sunac or if there is some government intervention behind the scenes, but, on the whole, it is a positive development to see that something is being done to resolve the situation.

This deal is still contingent on five conditions, one of which is reaching agreement with all Kaisa’s creditors. My interpretation is we’re seeing progress, and we’ll be seeing more dialogue with both onshore and offshore investors. At the very least, offshore investors are no longer being kept in the dark.

Luke Garner, JP Morgan: One thing I find quite interesting is that this really demonstrates the maturity of the high-yield market in Asia. This is, to some degree, an isolated event and, obviously, there was a reaction, but the market hasn’t completely shut down. If you think back over the last eight years of the high-yield market in Asia, we’ve seen periods where there have been complete shutdowns. That is an indication of the maturity, in terms of people being able to dissect credits, assess corporate risk and price that risk accordingly. The fact that deals are still coming to market, to me, is a good indication that this market has come a long way. It’s an unfortunate situation and there is a lot more to come out of it, but the market is still moving.

IFR ASIA: What do our portfolio managers make of this, then? Does risk need to be repriced in China property, or is this a contained event?

Jim Veneau, AXA IM: Well, this started out as a very troubling event. We were blindsided and, to some extent, it was idiosyncratic. The HSBC acceleration was idiosyncratic. What wasn’t – and far more troubling – was the introduction of something that could have become systemic risks. That is something that has always been latent in the China non-SOE space, political risk.

So how do we assess this? Kaisa was a Double B credit, so it’s still high yield, but the annual default risk at that rating is about 1%. As recently as November, Kaisa still had positive earnings results, so there was nothing on the radar that indicated that it was in any kind of trouble. This came completely out of left field. China property is a huge part of the high-yield asset class, so this had the potential of causing all kinds of problems and huge repricing – and it did for a while. It introduced volatility, spreads widened.

Where we have today is a dramatically improved situation because the issue of political risk has been taken on front and centre. You could say they were a little late, but, when push came to shove, the government did step in at some level. We still don’t know where, but somebody got tapped on the shoulder and told, “look, we don’t want this to happen, we’re going to smooth this over.” Now, we’re not out of the woods yet, and I still think there’s a reckoning here. Somebody traded bonds in the 20s, and now they’re in the 80s, so somebody’s unhappy and somebody’s going to litigate.

IFR ASIA: But who would you litigate?

Jim Veneau, AXA IM: Well, not to jump ahead here, but I think the fact that the HSBC loan accelerated and wasn’t disclosed is a big problem. That was material other indebtedness, and the terms and conditions were not disclosed. The rating agencies that did rate this bond should have had that information. They could have been more timely in getting that information and informing the market.

There’s a lot of blame to go around, but the bottom line is that there’s US$2.5bn of offshore debt, so this was widely held in the market. This could have been a huge issue. Where we are now is a relatively good place; I think the political risk has been put aside. This is a shock and a scare that will have some impact on the market, but, right now, it’s a learning experience.

Kenny Chan, Times Property: I totally agree with Jim, from an issuer’s perspective. We just released our latest earnings yesterday, and our chairman told investors that this had been a good lesson for the government – that you couldn’t just block everything so easily without a reason. Now, they have seen the consequences. They have seen people preparing petitions. They have seen the secondary market drop. They have also seen companies like ours where the pipeline has been affected. The consequences are quite severe.

We are expecting that the government may act less suddenly in the future when it has some issues with a company. They may give you some warning, or ask for further information.

We did quite a few non-deal roadshows last year. We went to London three times, Singapore four times and the US twice. Before the Kaisa case began, investors would just ask about the financials of the company: how expensive is your housing, how many units are you going to deliver. It’s very straight forward. But right after Kaisa ran into trouble, we went to Singapore in December. The first question was: where is your chairman? And the second question was: is he staying at the Four Seasons hotel?

These kinds of questions are really hard to handle for CFOs because it’s not about the company. It’s about the chairman himself or herself. So, these days we need the chairman to come out, but we can’t expect that for every investor meeting. It’s a dilemma.

Right before Kaisa, the bonds of Times Property were trading at 110 – one of the best performers in the market, with an effective yield of just about 10%. After Kaisa, they were at 96. That’s a 14%–15% yield. Luckily, we raised enough money last year, and we have no reason to issue bonds at 14%–15%. Investors still need to invest, and they can’t wait forever, but, this time, I think it will really take months to recuperate. We need more time to educate investors, and investors need more time to look at the market. I think the risk premium from now on will be much higher.

Haitham Ghattas, Deutsche Bank: In my mind, that is one of the lasting components of this episode. What is the appropriate risk premium that now has to be applied? In the past, the strength of the chairman’s local connections was perceived as a positive. We’ve flipped that on its head and the market is now more concerned about the implications of that connectivity.

To Luke’s point, I agree that the fact the market has somehow been able to work its way through is certainly a positive. Two or three years ago, I think this would have just shut the market down completely – for months. Nobody wants to bring up an old favourite like Sino-Forest, but the truth is it froze out industrial borrowers for six to 12 months. Yes, low-rated companies may find that their risk premium has gone up substantially and that the cost of capital is higher than they would want it to be, but the fact is that markets are open. You could go out, and real-estate companies today are going into the market to raise funding.

The key question for the longer-term is the appropriate premium for this political risk. The onus is also going to be on corporates themselves, through greater transparency and greater communication, to demonstrate to investors why their risk premium should be zero or negligible.

Alex Lloyd, Sidley Austin: I think that’s a good point and, to go to what both Jim and Luke were saying, if the market is showing signs of maturity then one of the obligations is on the issuers to catch up. Issuers are subject to disclosure requirements through their listings in Hong Kong. They have compliance and certificate requirements within their region, but these are frankly relatively weak. Issuers need the internal control systems to identify information that is in fact material and ensure that is appropriately disclosed in compliance with their obligations. Part of the maturing of the market is the maturing of these issuers to meet these obligations, to maintain the benefit of what they get from the market.

Michel Lowy, SC Lowy: To take a slightly different viewpoint, I think it’s actually counter-productive that the market has come back so quickly. I still think there’s a decent chance that creditors are going to be asked to PIK their interests for a period of time as there’s no cash available and because everyone needs to participate in order to avoid a blow-up. The sign that the market is sending to Beijing and to borrowers is that, after all, if you find a Chinese solution it is not really such a big deal.

And it is a big deal. It is a big deal that there have been a number of borrowers over the last year where we suddenly found out their numbers were not the actual numbers. It is a big deal that political intervention can massively destroy value for creditors. And it is a big deal that one can’t really analyse that. We can do all our homework, but, the reality is, you can’t put a price on that risk.

I think it’s dangerous that the market has come back. Obviously, as a market participant I feel good. We’re all happy that the market has come back when we look at our positions, and we are happy from a primary and a secondary standpoint, but I think it increases the risk that we’ll see more Kaisas in 2015 because the sign we’re sending is that it’s not such a big deal.

Luke Garner, JP Morgan: To Kenny’s point, though, if you look at where secondaries are now versus December, the recovery is still not complete. There’s still a massive disparity from where we were. Maybe, it’s just a learning curve in terms of where the market views that political risk.

Haitham Ghattas, Deutsche Bank: I hear your point, Michel, and, perhaps, there’s a chance that people will look back and say it wasn’t so bad – unless you’re the investor who sold at 20 and bought at 105 – but, on the other hand, I do think it has added some urgency for investors, in terms of the questions they will want to ask, the amount of diligence they want to do and, ultimately, the price they are going to charge.

I don’t disagree that the market, in its evolution, may need to see a credit event or two to really test what would happen, but, on balance, the market is demonstrating that it is listening, and it is pricing that risk to some extent. Going forward, there will be a differential between borrowers who are able to access markets at attractive levels and those who can’t. There will be a greater bifurcation. Those issuers able to communicate clearly with their investors on a regular basis will be rewarded.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: I agree with a lot of what’s been said and, at its core, it’s good to see that the market hasn’t been shut completely. It’s interesting to see that Chaoda’s equity has just started trading again after being blocked for all those years, while, in Kaisa’s case, that has really been sped up by the delisting put on its CBs. That set a much earlier deadline for the trading halt to come off and, without that, we would probably still be in an unknown situation. So, a diversified mix of funding options has brought the matter forward.

I think it’s good that the bonds are not back at par. It is important that the message gets sent that there is credit risk involved. The big issue here is that it’s the Asian consensus story. Everyone has property exposure. It’s the biggest, deepest, most liquid part of the market. It’s very much an issue around concentration and the dominant role that this one, capital-intensive sector has to play in our market.

There are pros and cons from this whole episode, but it does highlight that just simply having half your exposure in Chinese property, even though it’s such a pervasive sector, doesn’t make for a healthy market.

Alex Lloyd, Sidley Austin: This is really as much a question as a comment. The question I have is whether the risk profile is actually any different. I mean, this product has always been deeply subordinated. If you look at the relatively few restructurings that have happened in this market in recent years, whether it be Asia Aluminum or Sino-Forest, what you referred to as a “Chinese solution” has, to some extent, always been the solution. It’s just that this is moving faster. We’re getting towards the same end, in that offshore creditors are deeply subordinated and have relatively little power. The risks haven’t changed.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: The risks may be new to some, and they may not be priced correctly, but you’re right. The risks are not new. It’s hugely idiosyncratic and results have been mixed. Some have been good, some have been bad and that’s why you get paid more. That’s why there is a structural premium. That’s why even investment-grade Chinese SOEs, banks or SBLC deals have to pay up.

Investors will insist that they have protection in place, but only to the extent that they can. We’re seeing the potential demise of the CAMA account for one different jurisdiction, and maybe that’s going to have to return here, to ensure that some protection exists and at least some offshore cash is maintained so there is some semblance of recovery.

The way to compete for capital from offshore investors is price. That premium has to be there. If you’re not willing to pay up, or if it’s not sustainable for you to pay up, don’t come to market, for one. Two, check your business model to see if it’s sustainable and, three, communicate with investors. Be clear, open and transparent.

Luke Garner, JP Morgan: Just one factual point. You could look at Kaisa, Neo China or Greentown, and this sector has had a relatively soft landing in terms of the situations that have come up in the past. Now, maybe that’s a function of just the importance of the property industry in China, but it’s very different from the industrial sector if you compare the two.

Ying Wang, Fitch Ratings: Structural subordination does exist in every offshore Chinese bond, but the sector does make a difference. How much you get paid at the end of the day in a recovery situation is probably fairly low, as we have seen from cases, such as Asia Aluminum and Suntech Power. But, in the real estate sector, so many Chinese developers are dependent on offshore financing, and it’s such an important sector for the economy. You would have to think that this sector is more likely to be supported by the government, that the government will take a more benign view on offshore creditors. Of course, I’m not saying that, if you invest in Chinese real estate, the government will take care of you.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: There has to be a mechanism for removing moral hazard. And that’s why, in some respects, it’s a good thing that there hasn’t been some magical solution that has brought everyone back to par. You can’t have a sustainable capital market or even a sustainable economy where that perception exists. There needs to be debt forbearance, there needs to be loss, there needs to be a workout in certain circumstances that are justified.

IFR ASIA: You’ve just described the onshore credit market, where there is no concept of default.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: I know and this is not consistent. There’s a major issue here. If you think about the medium and longer term, making sure that offshore creditors can provide the capital that China needs, but also appreciate the risk and the compensation that goes with that. It is important for us that this is not a complete and utter bailout that takes everyone back to par. To me, a muddle-through scenario would take us further back.

Jim Veneau, AXA IM: This is far from a bailout scenario and, I think, what remains troubling here – and we haven’t done a full post-mortem on Kaisa – is the lack of communication on Kaisa around the time of the announcement to the exchange. This could have been very simply dealt with and very simply clarified, and we don’t know if there was any nefarious intent there by someone in this, because it is very clear to see that the lack of transparency was driving the bonds down. As I said earlier in this discussion, bonds traded at very low levels. Those people can’t be bailed out. Somebody bought bonds at those levels and has benefited from a rumour-fuelled rally.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: There’s no doubt that offshore minority investors were put at a significant disadvantage. As an equity investor, you’re protected, essentially, because the exchange was closed to trading. Offshore minority creditors, absolutely, were put at a disadvantage.

Jim Veneau, AXA IM: This story still has a long way to run. Significant investor losses will attract scrutiny from a lot of market observers.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: I don’t think these situations are unique here, but it’s much more obvious.

Jim Veneau, AXA IM: It’s the order of magnitude here – we’re talking about US$2.5bn.

IFR ASIA: Fortunately, we have a gentleman here today who runs a distressed-debt trading house. Michel, can you tell us a bit about the dynamics here?

Michel Lowy, SC Lowy: Well, as Jim said, it’s the lack of information. You have a corporate that is seen as one of the darlings of the market and suddenly, overnight, the assets are frozen and people have resigned one after the other. There’s no communication. As a bondholder, you know that you’re structurally subordinated. In my opinion, owning Chinese property bonds is owning subordinated equity. You have absolutely no leverage, you sit offshore and you have no information. As a fund manager, you have to make a call. For most market participants, you weren’t really in a position where you could analytically look at the pros and cons and make a sound investment decision. That means some people exiting, and others will say, at 30 cents, I can triple my money if I’m lucky or it will go to zero. That’s what some people did, and some people benefited.

The other question that it raises for me at the macro level is this: is the entire Chinese bond market going to reprice at the same time as the industry in China is suffering? Can corporates afford that? When a borrower agrees to borrow from you at 20%, that’s not necessarily good news. It may mean that he is totally desperate and that he has no intention to pay you back.

I think a part of the analysis for all of us is what is the right price for corporate debt from China, and can those corporates afford that? Can they generate the kind of gross margin that will still allow them to generate the profit to refinance a few years out? We all say the market needs to reprice, but we don’t know what the right price should be. We don’t have enough history.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: We do have sufficient history to know that a premium is involved. These issues of information asymmetry and structural subordination are not unique to China, by any means. It’s one of the risks that goes with emerging markets, and why you should expect more return as an investor. The Asian property space has, historically, always traded at a premium. On probably two occasions over the past seven or eight years, ilt has traded flat, and clearly it didn’t stay there for very long.

One big positive for me from all the recent events is that there was at least some trading. We don’t just want a consensus trade where everyone is buying Chinese property. That’s really been the momentum trade in the past few years. So, the fact that you’re seeing a secondary market is actually fantastic. There have been previous circumstances where you go to 30 or 40 cents and there is no trading, no liquidity, nothing. So, that, in a sense, is a good thing and it is especially great in our market that, where there are liquidity pressures in the secondary market from the big global banks, you now have these smaller, agency-type brokers able to come in and fill the gap. That is fundamentally a very good thing.

Michel Lowy, SC Lowy: I certainly agree with that point!

IFR ASIA: So how is liquidity developing? We’ve heard there was trading, but the jump from par to 30 cents suggests there weren’t many buyers out there.

Jim Veneau, AXA IM: This did properly leg down, it just legged down very quickly.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: The trading pattern I would argue is common, or at least not unusual, but the volume of trading at 30-40 cents, based on the information we have, was much higher than normal.

Jim Veneau, AXA IM: The market speak was that the private banks were coming in and buying on the cheap, and that it was real money that was selling.

Haitham Ghattas, Deutsche Bank: We’re talking about US$2.5bn of securities out there that actually trade. It’s pretty difficult to analyse the trading statistics, but I agree with Bryan’s point that you could get a two-way price pretty much every day of January on Kaisa bonds, which, in itself, is quite impressive.

From a longer-term standpoint, one of the things Michel mentioned earlier is going to be more interesting in my mind, and that’s the confluence of more difficult economic conditions onshore – slowing markets overlaid with rising offshore interest rates and this additional risk premium. Does that lead to greater bifurcation of the ability of borrowers to access markets?

IFR ASIA: Well let’s broaden it out from there to the outlook for China credits more generally. Kenny, you mentioned that prices are too high to justify coming to market at the moment. Have you seen anything beyond Kaisa to justify paying that risk premium?

Kenny Chan, Times Property: To be honest with you, last year we did our first bond at quite a high premium because the market was bad. We priced our first bond at 12.625%, which was the highest in our company’s history. Since that time, I’ve realised that investors don’t just look at yield. Investors are now focusing more on compliance, the other investors’ background and the background of the chairman.

Last year, we did a CB with the IFC, part of the World Bank, and Fortress. Right after this deal, we got very good feedback from the rating agencies and from the market, because these are good quality investors, who did a lot of due diligence on us. I saw my bond trade up at least six or seven points from 101 to 107–108 and stay at a high level. That taught us a very good lesson that we have to find some good names. We have started talking to some other good quality names, hoping that they will invest more capital into our company. The actual amount may not be that significant, but it would send a very good signal to the market that our company is still looking very good.

You can also see in December that some property companies did private bonds with some asset-management companies in China, or a syndicated loan. High yield is no longer our only solution. We’re looking for JVs; we’re looking for CBs; we’re looking for syndicated loans. If the market remains so high, we’re definitely not doing any bonds, because we have to report to our shareholders and we can’t give them too serious a hit to our net margin. These days, I would expect maybe the investment-grade names will come out because their funding costs are relatively cheaper, and they can send a positive signal to the market that the sector is still relatively stable. When you get down to Single B, not everyone will be able to come out because investors are smarter these days. They know that, if you pay 15% or 16%, it means something.

Alex Lloyd, Sidley Austin: I think, Kenny, what you’re saying is that there is a real value to transparency. You can see a margin return that grows the better you run the company and the better the internal controls. Companies can really benefit from open communication, and I think that’s particularly the case as this market matures.

Ten years ago, high-yield was often the only source of significant offshore borrowing these companies would do – which is kind of weird if you think of how high-yield developed as a mezzanine product rather than a primary source of funding. That’s changing and, as that changes, you get a broader mix of creditors, and keeping those guys happy – and informed – is going to have a real economic return for the issuer.

Luke Garner, JP Morgan: To the question on whether the industry is being forced to issue at excessively high rates, one thing that is different today in this dislocation we’re seeing is that a lot of the issuers actually dealt with the refinancing that was required in 2013 and 2014. If you look at the bonds maturing this year, a lot of that has already been dealt with. There are a number of issuers that can afford to wait for yields to return to a point they are happy with. I don’t think there is that urgency we saw in maybe the last two or three years, when issuers had a ticking time bomb in terms of maturities.

IFR ASIA: Let me flip that back at you, then. Why would it make sense for a company like Evergrande to come to market today?

Luke Garner, JP Morgan: Property markets are very capital-intensive and a lot of these developers have very high margin businesses. Issuing at a level that an industrial may think is too high may still make sense to a developer because they can get the proper return on that investment. It’s very much a case-by-case dynamic in terms of what is the right level to issue at. The property market in China is also massive. The companies we’re talking about that are listed and have done bonds are the upper crust. They are established and, in a declining market, they may be the consolidators.

Haitham Ghattas, Deutsche Bank: The dislocation we saw, although troubling from a markdown perspective, was exactly that. The bonds were marked down and then marked back up again. It wasn’t redemption-driven selling, but, as a consequence, you had a drastic reduction in primary supply. If the investor base is flat or slightly up in terms of the cash they are sitting on, from redemptions and a slow primary market, then actually there is a large amount of cash to put to work. So, to Luke’s point, for those developers where yields are actually still compelling from a business model standpoint, it’s actually a good opportunity to come to market, while there is substantial capital to be put to work.

And as you look at the macro risks that could be on the horizon – whether it’s Greece, whether it’s Russia and Ukraine, whether it’s South America and the changing dynamics of some of the crossover corporate borrowers there – there could easily be a very large impact on market conditions. If you’re comfortable with the yields at these levels, it’s a prime opportunity to raise money.

IFR ASIA: Ying, let’s bring you in here on the macro outlook. Is the next driver of Chinese issuance going to be consolidation?

Ying Wang, Fitch Ratings: Well, for the property space I do agree with Luke that there is more consolidation to come. It’s a massive sector in China. From a macro perspective, the central bank is taking a relatively accommodative position on its policy. So, it looks like credit conditions onshore are going to improve for developers and banks will probably be more willing to provide construction loans. But the banks will prefer to lend to the bigger guys and even the onshore bond market is restricted to the better-quality, listed developers. So, the little guys, the weaker guys, are going to get eliminated eventually. Some of them may have good quality projects and the bigger developers are going to go bottom fishing. There is a need for capital and a need for refinancing. You’ll see the big developers coming out to issue this year.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: I think that’s a general theme for China, where you have slowing growth and a maturing market. Property, in particular, is maturing from a 20%–30% year-on-year growth in floor space to much more sustainable levels.

The same can be said from an industrial perspective, where the heavy capex period in the cycle is over. We’re seeing a lot of corporates actually cut down on capex, and some of these will be turning free cash flow positive for the first time. That’s actually an excellent thing for creditors, as long as the pricing’s right.

The big negative, of course, is that, while it’s rational for an individual company, it is bad for the broader economy as a whole. So, we need to be selective there. We’re expecting more M&A, and we’re definitely expecting more credit events over the next couple of years.

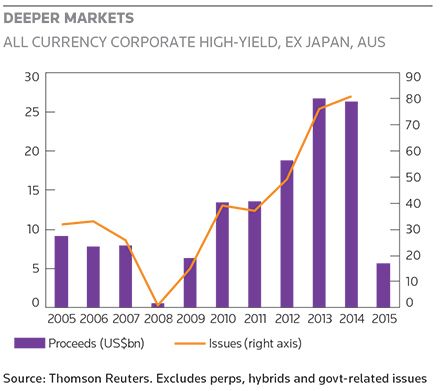

Haitham Ghattas, Deutsche Bank: I don’t think we’re talking enough about industrials regionally. We’re still in the middle of some of the highest growth markets anywhere in the world, and there is literally just a smattering of companies at this point that have come to market – notwithstanding the incredible growth we’ve seen in corporate high-yield issuance. If you go back five or six years, this market was US$5bn–$6bn a year. Go back three years, it was US$15bn–$17bn, and the last three years we’ve seen volumes of US$25bn–$35bn. We’ve come an incredibly long way, but we’re still only really scratching the surface.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: We’re also starting to see new regional growth drivers from services and other, less capital-intensive industries. We’ve seen that with car rental issues recently, for example. At the moment, they’re able to get away with a lower costs of funding than when the industrials started to develop; whether that will persist we’ll have to wait and see, but the Asian debt capital markets are following two or three years after the equity markets in terms of allocating capital to where the growth is coming from. China property, in five years time, will still be a large part of the market, but, hopefully, far smaller in percentage terms than it is today.

Ying Wang, Fitch Ratings: I’m very much looking forward to seeing new sectors come out. I do think it will be more consumer-oriented and more focused on service sectors, such as CAR Inc, which we rated recently.

IFR ASIA: That’s an interesting deal, but it looks like they still had to pay up to get it away.

Ying Wang, Fitch Ratings: Well they had to, but, if you look at the original price guidance, they got investors to come down inside 7%. There’s definitely demand for these kinds of credits. They’ve got a good story to tell.

Luke Garner, JP Morgan: If you back up three or four months, as well, you have the first deal from a Chinese auto OEM – Geely Auto. You saw Nexteer Automotive, which is Chinese-owned, but US-based. To Bryan’s point, these are new credits to the market, but they are very solid. It’s testament to the diversification that is coming with the maturity of this market.

Michel Lowy, SC Lowy: It’s not just sectors – and I totally agree that’s a sign of maturity – it’s also countries. Last year, we had significant growth of the Indonesian high-yield market, and the first few issues in India. That could very quickly become a significant high-yield market. One of the big positives of the last year is that we’ve moved from being a market that was heavily dominated by China property to one that is slowing migrating to different countries and different industries. That’s really the part of the market that is growing the fastest.

Bryan Collins, Fidelity: Historically, we’ve had a chicken-and-egg situation where people shied away from a new credit because it didn’t have comps, and it was just easier to buy another Chinese property bond. Obviously, we now realise that in itself has inherent problems.

We are seeing new companies and new sectors come to our market, but they’re not new businesses. We do have global comps, and global law firms and analysts that can help you understand the business. Also, as Asian companies get acquired by large international companies and as they become the ones doing the acquiring overseas there is some overlap there. Once you get your head around a new sector that really opens the door for more. I’m hoping that the momentum we’ve got on that at the moment is sustainable. I’m quite encouraged.

To view all special report articles please click here and to see the digital version of this report please click here .

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@thomsonreuters.com .