Private capital will play its part in financing China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. But how quickly infrastructure owners can fire up the capital markets to bridge the investment gap is up for debate.

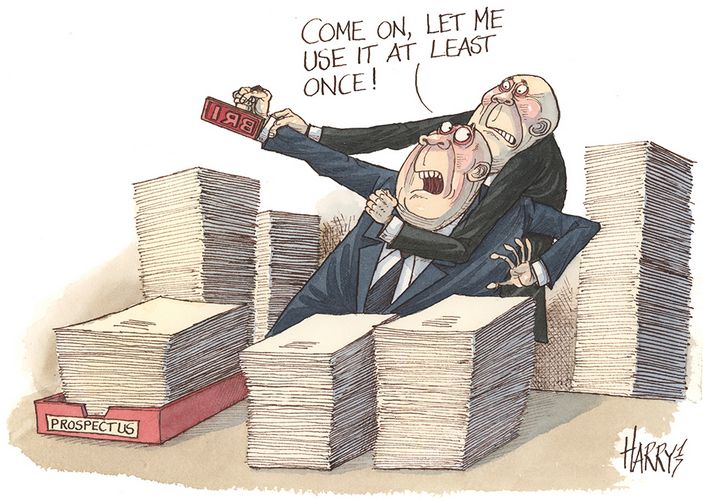

It has taken the Chinese authorities some time to settle on an English name for President Xi Jinping’s signature trade and development policy. What started in October 2013 as the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road and was labelled One Belt, One Road, or OBOR, at first is now officially the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

What was never in doubt, however, is the sheer scale of the plan. The parallel development of an overland trade route from China to Europe via Central Asia and a maritime link to the Mediterranean via the Indian Ocean embraces over 65 countries, 69% of the world’s population and almost a third of the global economy.

It brings with it the promise of huge outbound investment as China moves to cement its position as a global economic power.

That kind of ambition does not come cheap.

Estimates for the total cost of the scheme vary enormously.

DBS reckons that the transport infrastructure investment alone will exceed US$200bn over a five-year period. This is more than double the current batch of transport infrastructure projects under development in the ASEAN region, the bank noted in a September 2017 briefing.

In early 2017, the Chinese government said that BRI-related projects worth a combined US$1trn were already planned or under way, but that the full initiative had “an expected lifespan investment of US$4trn to US$8trn”. (The latter figure represents “the cost of building the infrastructure that developing countries in Asia will need in order to maintain the economic growth that will lift people out of poverty in the next decade,” to quote the official China Daily.)

SILK WALLET

There is plenty of policy wallet behind the initiative. Backing the objectives, the Chinese government established the US$40bn Silk Road Fund in 2014 with shareholders comprising China Development Bank, China Investment Corp, Export-Import Bank of China and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange.

There is also the US$100bn Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which opened its doors for business in January 2016, and the Shanghai-based New Development Bank, which aims to invest US$100bn of resources for development projects in BRICS countries.

Public money, however, could not finance the scheme on its own.

“The upper end of the estimations would not be covered by the entire global foreign exchange reserves,” said Becky Liu, head of China macro strategy research at Standard Chartered. “It is clear that the participation of the private sector will be crucial in the success of the initiative.”

Sooner or later, it will fall to the capital markets to mobilise private investment into funding the exercise. That expectation is creating a great deal of noise – if not excitement, about what kind of shape the fundraising will take.

“It will be a combination of both loans and bonds and will depend on liquidity and pricing,” said Ashu Khullar, Citigroup’s head of capital markets origination for Asia. “So shorter tenors are likely to be loans and further out past five years via the bond market. We also expect to see a number of project financings related to the Belt and Road too.”

It is a mouth-watering prospect for bankers in Asia, but realising the potential of the expected onslaught into the capital markets might take some time – particularly as regional financial markets need developing just as much as the trade routes.

“There are opportunities for private sector involvement,” said Liu. “But there are also a number of challenges to overcome.”

NEW FRONTIERS

Although the initiative covers two-thirds of the world’s population, its scope is just a third of the global economy. This discrepancy points to some of the major problems that need to be addressed.

Most of the BRI infrastructure projects will be newly built and built in the lesser-developed parts of the world; not the conditions to attract long-term private finance unless there is sufficient risk mitigation. Projects will need to be “bankable”.

Greenfield projects constructed in frontier markets come with a whole host of risks, not least political. Already, BRI projects have run into issues. In November 2017, for instance, both Nepal and Pakistan withdrew from MoUs signed with China to build dam projects.

It highlights the need for public sector support in creating the right level of security and the right kind of economics to “crowd in” private investors.

“The key thing for mobilising private investment for the Belt and Road Initiative is to find ways to reduce the capital cost of investing,” said Nan Luo, head of China for PRI, the investor group encouraging responsible investment. “Through financial innovation, international cooperation and through reducing risk.”

In other words, aligning private capital with other sources of financing and risk mitigation: government participation; guarantees; policy banks and multilateral development banks (MDBs) taking on the majority of the risk; and financial innovation such as project finance, project bonds and securitisation.

RISK APPETITE

For the current set of projects in progress, there is a big gap between the assets that need financing and the risk appetite of international investors. The majority of the financing of those projects so far emanates from within the Chinese policy-driven banking system and will likely continue to do so.

“The projects will initially be driven by Chinese money,” said Hilary Lau, corporate partner at Herbert Smith Freehills. “There won’t be enough use of project finance to begin with as it’s a new concept to the Chinese banks. It will take some time before financing is tailored to international standards.”

It’s not all bad news, despite the fewer numbers of international banks lending long-term in Asia. The local currency markets remain liquid and the Japanese and regional banks are still actively funding projects around the region. There are also hopes that persistent low long-term interest rates might tempt some of the region’s pension funds into the market, as is the case elsewhere in the developed world.

Credit enhancement products have facilitated the flow of institutional investment into projects throughout Europe, while the Elazig Hospital deal in Turkey is an example of how efficient allocation of risk can work in emerging markets.

The Elazig package included political risk insurance, and credit enhancement through a liquidity facility provided by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The government-guaranteed offtake agreement and foreign currency risk hedge closed the circle. It resulted in bonds attaining an investment grade rating – two notches above the sovereign.

“There is potential for an Elazig type deal to be replicated in Asia,” said Vivian Tsang, North Asia head for project and infrastructure finance at Moody’s. “For the right transaction, with an appropriate allocation of risks over the lifetime of the project, then there is demand for project bonds.”

As if to reinforce that optimism, the first investment-grade and the largest rated amortising international bond for an infrastructure project in Asia since 2000, was launched in August.

“The key thing for mobilising private investment for the Belt and Road Initiative is to find ways to reduce the capital cost of investing.Through financial innovation, international cooperation and through reducing risk.”

The US$2bn senior secured notes from Indonesian power producer Paiton Energy, launched via Minejesa Capital, saw massive interest from investors around the globe, with an order book said to exceed US$9bn.

“It shows that the use of project bonds is possible again in Asia,” said Moody’s Tsang. “And while this is a brownfield deal, it shows there is potential for banks to recycle loans into the capital markets.”

The Paiton deal reveals there is institutional demand for project risk but only parts of that risk, and only at the right price. It’s a start but, for the time being, the question is how to bridge the financing gap in the short term.

For now, China is taking the strain: policy banks and insurance providers with the big four commercial banks standing behind them.

“It’s just not sustainable to expect the banks to keep writing cheques,” said Tsang. “You can’t just expect the Chinese banks to provide all of the financing.”

If that is the case, then there needs to be a change in behaviour within Chinese banks more used to lending at the corporate level rather than in the fashion of true project financing.

There are signs of movement.

“Chinese banks want to tap into foreign expertise,” said Tsang. “They would still bear the majority of the funding but they want a diverse group of local and international banks to join in the financing.”

BONDS THAT BIND

While there is potential for project finance and project bonds in the future, there is already some excitement in the wholesale bond markets.

“The reality is that the bulk of private sector investment for the near term will be indirect, and denominated in dollars and euros,” said StanChart’s Liu. “As sovereigns, policy and commercial banks, and state-sponsored enterprises look to raise funds through bonds issued into the most liquid markets.”

Illustrating that sentiment was Bank of China, which expressed its commitment to the cause in 2015 with a US$4bn multi-currency bond, to become the first issuer of bonds linked to investment in the Silk Road project.

“We are already seeing plenty of transactions coming to the international markets,” said Citigroup’s Khullar. “One example was the Bank of China multi-tranche and currency … that provided funding for many of the bank’s branches along the Belt and Road.”

The bonds were launched by the bank’s overseas branches in Hungary, Hong Kong, Singapore, Abu Dhabi and Taipei, tapping US dollars, euros, Singapore dollars and renminbi in a variety of formats including offshore renminbi and four tranches going into Taiwan’s Formosa market.

China Construction Bank was up next with a Rmb1bn two-year Dim Sum deal that was dual listed in Malaysia and Hong Kong.

It looked like the market was on the cusp of a new internationally recognised asset class. So much so, that a Silk Road Bond Working Group was set up in Hong Kong at the end of 2016 to help drive the development of the instruments.

Labelling securities as Silk Road bonds was described as a “crucial development” for the BRI at the time, with hopes that the market could benefit from a similar set of “use of proceeds” principles as has supported the growth of green bonds.

Silk Road bonds as an asset class sounds good in theory, but there is a major problem in terms of definition.

“What is a Belt and Road project?” said Herbert Smith’s Lau. “It’s a fundamental issue. What does it mean? Is it anything along the Silk and Maritime routes built with Chinese money? There’s no official list.”

That level of ambiguity has put the notion of Silk Road bonds as a specific asset class on hold. There remains, however, strong interest in taking exposure to BRI.

“What is a Belt and Road project? It’s a fundamental issue. What does it mean? Is it anything along the Silk and Maritime routes built with Chinese money? There’s no official list.”

“Some fund managers are already setting up dedicated Belt and Road funds and also some of our private bank clients are interested in investing in Belt and Road projects,” said Khullar. “It may be some time off before Belt and Road bonds are a standalone asset class, but there is clearly a growing interest in investing in Belt and Road-related financial instruments and the investment opportunities around it.”

It means that the bonds will keep flowing as banks and sovereigns along the Silk Road seek to raise funds for BRI-related development. It will likely spur the development of local currency markets and associated hedging instruments as the renminbi becomes more important for finance and trade throughout the region.

That’s good news for the Panda and Dim Sum bond markets. They have already been tapped in the name of BRI and more deals are in the pipeline.

Maybank and Hungary have launched Panda bonds and the Philippines is waiting to make its maiden appearance in the Chinese onshore market. The further development of the renminbi capital markets will be a welcome by-product of BRI financing.

Opening up the bond market to attract investors as well as borrowers will also limit the capital outflow and alleviate pressure on the currency – a consistent bugbear for the Chinese authorities.

Regional financial centres also stand to benefit from BRI. They are the conduit to liquidity in the international markets and the locations to attract all the ancillary business and hedging activity associated with foreign currency transactions.

They also have the legal systems and depth of international expertise that will be important to the project finance, M&A and debt take-outs that will eventually – and inevitably, feed through.

There’s no doubt that BRI financing will make its way into the capital markets but there is still some way to go before the floodgates are opened.

What is clear is that the bulk of the first wave of projects will be financed with Chinese money – government, policy banks and commercial banks, and these will be regular visitors to the bond market.

“We expect to see an increased flow of transactions both in dollars and local currencies across the Belt and Road as more financials and companies look to tap for cost effective financing needs related to it,” said Khullar.

It all sounds exciting, but it’s not there yet.

“The key thing for mobilising private investment for the Belt and Road Initiative is to find ways to reduce the capital cost of investing.Through financial innovation, international cooperation and through reducing risk.”

To see the digital version of this report, please click here