Fintech has started making inroads into retail banking and payments, but complex and heavily regulated capital markets are likely to prove a tougher nut to crack.

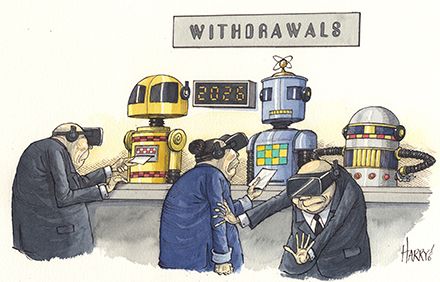

With bankers seemingly quitting front office roles in droves to join fintech startups, one could be forgiven for concluding that Asia is on the cusp of a revolution in the application of technology to the capital markets.

For now, however, the focus is on retail banking. Venture capital money has been pouring into peer-to-peer lending platforms, remittance companies, robo-advisers and crowdfunding sites that are gradually starting to chip away at incumbents’ market share.

For wholesale banking, the role fintech will play is less clear, although things could change quickly.

“Most of the current venture capital funding and talent has gone into retail: peer-to-peer lending, robo-advisory, payments, etc,” said Jan Bellens, global emerging markets leader and Asia banking leader for banking and capital markets at Ernst & Young.

“There are a number of reasons why that is the case. There is less talent that understands the capital markets. You are also dealing with critical infrastructure where billions or, in some cases, trillions of dollars of funding flow each day so there are obviously issues regarding trust and security. Nonetheless, we are starting to see a change.”

According to data provided by the Boston Consulting Group, out of roughly US$97bn in venture capital investment in fintech that the consultancy firm has tracked since 2000, only US$4bn has gone specifically to capital markets fintech firms.

There are a number of reasons for this, including the relatively high start-up costs for operating in the capital markets and the high degree of expertise required.

The most obvious reason though is that the prospect of mass adoption in retail banking is far higher, with numerous venture capital firms on the lookout for what the Boston Consulting Group describes as the ‘Uber moment’ of finance.

While the profitability and reputation of the major banks have nosedived in recent years, today’s investment banks remain highly specialised and subject to strict regulations, which reduces the likelihood of disruption from outsiders.

“In retail financial services, the fintech firms have often taken on the traditional players by disintermediating them,” said Bellens. “But while there are a few opportunities for disintermediation, our view is that the relationship is likely to be more collaborative in investment banking.”

Origin of the species

One of the best known fintech firms operating in the capital markets is Origin, which was founded by former Nomura traders Raja Palaniappan and Robert Taylor.

The company aims to provide a marketplace for frequent medium-term note issuers and investment banks. By creating a centralised platform that allows issuers to upload their terms and access multiple dealers, the London-based startup aims to simplify the procedure for issuing private placement debt and ultimately provide a benchmark for the industry.

The company held its soft launch earlier this month with a number of dealers and issuers joining the platform and aims to expand in Asia once it has established a foothold in the European debt markets.

“We’re establishing ourselves in Europe but the next step will be Asia,” said Palaniappan. “The MTN market takes advantage of EMTN and GMTN documentation, which allows issuers to sell all over the world except in the US. Given the investment flows between Asia and Europe, it makes sense to expand into Asia.”

The company envisages its role in improving access to information in the MTN markets and thereby facilitating deals as opposed to disintermediating banks.

“There are a lot of issues to address for any issuance including clearing and settlement risk, which the banks are well-positioned to deal with,” said Palaniappan. “In addition, the dealers are also able to provide swap functionality so we don’t see ourselves as a rival to them.”

Blockchain

The primary purpose of a lot of fintech companies engaged in the capital markets has been to address inefficiencies with existing processes, in particular in the back offices, which the major banks tended to ignore during the boom years.

Deutsche Bank’s chief executive John Cryan was frank about this when he talked about how the bank had pioneered a number of complicated and exotic financial products but was still employing large numbers of contractors for data inputting and other mundane tasks.

Blockchain, the distributed ledger system behind the crypto-currency bitcoin, is seen by many as a solution to issues surrounding processing and settlement.

In October, Commonwealth Bank of Australia and Wells Fargo completed the first trade finance deal between two unrelated banks using blockchain technology, for the US headquartered cotton trading firm Brighann Cotton.

The deal included a physical supply chain trigger to confirm the geographic location of goods in transit before a notification letter was sent to facilitate release of payment.

For some, there are expectations that blockchain could be applicable to capital markets deals.

“This is an early stage experiment but we think using blockchain technology for corporate bond issuances is worthwhile exploring,” said Michael Eidel, executive general manager of cashflow and transaction services at CBA.

“If you think about payments and remittances, blockchain is certainly applicable. We are currently talking to potential partners about this.”

Partnerships

The Brighann deal was also noteworthy due to the number of parties involved, which included the company’s two relationship banks along with blockchain startup Skuchain.

A number of investment banks have introduced accelerator programmes to partner with fintech firms to develop and fine-tune the latest disruptive technologies, with Barclays’ programme one of the better established. This is more efficient, many banks argue, than going it alone in a field where they lack sufficient expertise.

“If you look at the history of the financial services industry, most banks haven’t been too successful in developing their own technologies, with the possible exception being Goldman Sachs’ dark pools platform,” said Zennon Kapron, founder at Kapronasia.

“My expectation is that a lot of the solutions are likely to come from some third party or a consortium of banks coming together.”

The most notable example of banks pooling their resources has probably been R3, a consortium of around 70 financial services institutions that was set up to develop an open-source blockchain platform.

A number of banks including Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and National Australia Bank have recently exited the consortium though, which has been viewed by some as an example that efforts by banks to disrupt themselves are rarely fruitful.

Future of banking

The aim of most fintech companies operating in the capital markets is to find pockets of opportunities they can exploit rather than aim for wholesale disintermediation.

This dovetails with another recent trend: the decline of the universal banking model.

The number of full-service, global investment banks is rapidly declining due to increasing cost pressures. Instead, banks are increasingly defining themselves by their expertise in certain products, regions or services.

Palaniappan told IFR that this is an area where companies like Origin can thrive. Once the platform reaches a critical mass, it will be able to connect European issuers with dealers in Asia, for example, even when the banks have no presence beyond their local markets.

The last few years have also seen banks outsource commoditised business processes such as regulatory reporting or trade reconciliation for cost reasons.

Once blockchain moves beyond the proof-of-concept stage, this is likely to be become more common with banks relying more upon external platform providers.

For some, the potential of blockchain goes beyond improving existing payment and settlement processes. It will help facilitate investment, they argue, in markets like precious commodities, which suffer from lack of trade protection because of the absence of a central ledger.

This is likely to take longer to come to fruition, but even if this proves to be the most revolutionary application of blockchain, it suggests that investment banks need not worry about being disintermediated just yet.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here